As reading habits evolve alongside technology and lifestyle shifts, South Korea’s “text hip” moment may be less about returning to old routines and more about inventing new ways to engage with books.  When Gim Ji-min arrived at the Seoul International Book Fair 2025 in June, she thought the social media hype was overblown.

When Gim Ji-min arrived at the Seoul International Book Fair 2025 in June, she thought the social media hype was overblown.

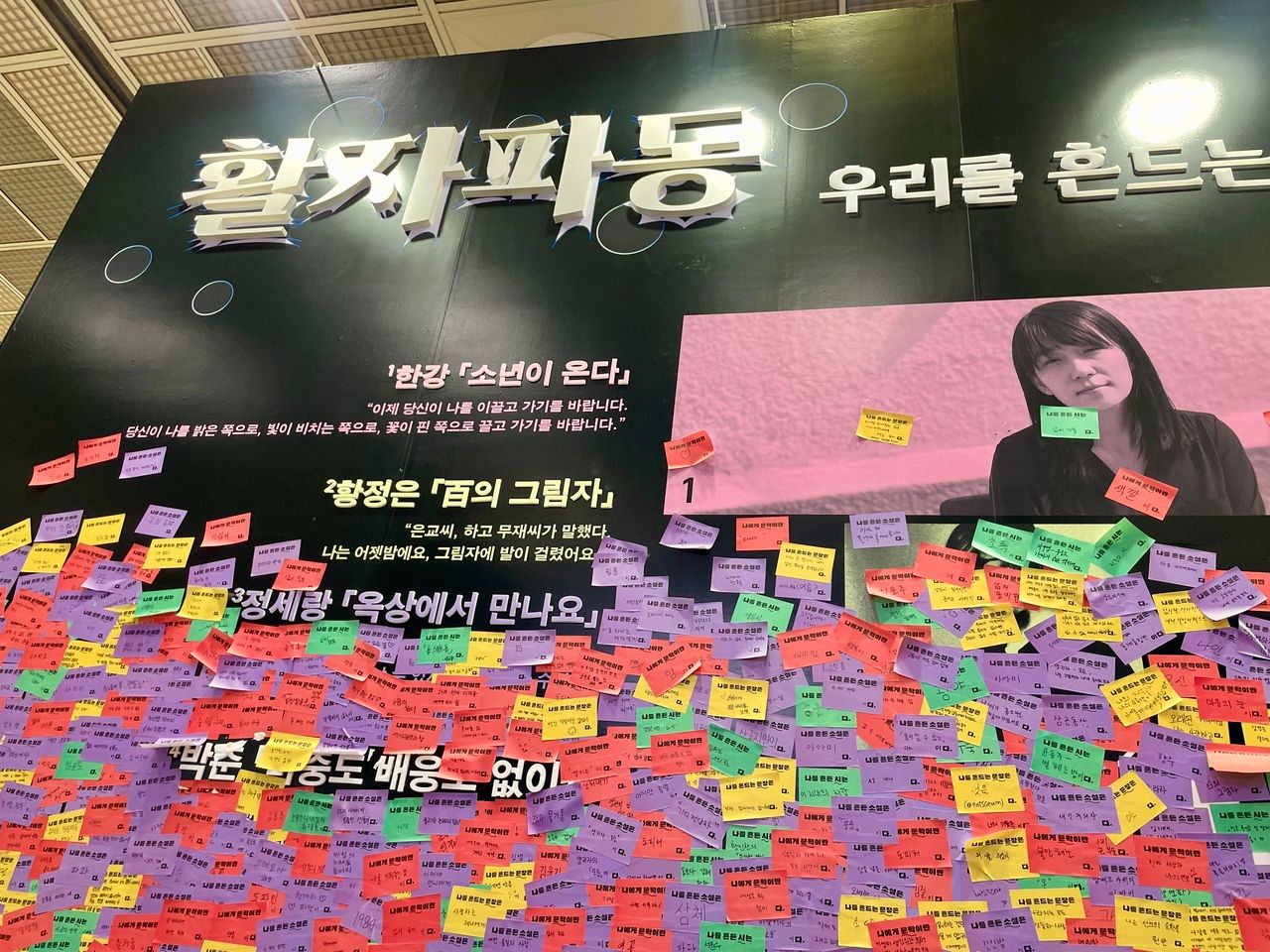

Gim wasn’t the only one caught off guard. Over five days, more than 150,000 people swarmed Seoul’s Coex convention center. Tickets sold out weeks in advance, forcing organizers to issue apologies. Whispers of scalpers reselling passes at triple the price spread like wildfire. The crowd was dominated by women in their 20s and 30s, eagerly snapping pics of sleek book covers and quirky literary merch. Gim doesn’t fit the mold of a bookworm. “I read a ton, especially nonfiction and social science stuff, but I’m more of a borrower than a buyer,” she admitted. Yet the festival vibe of the book fair reignited her desire to actually purchase a book.

Gim doesn’t fit the mold of a bookworm. “I read a ton, especially nonfiction and social science stuff, but I’m more of a borrower than a buyer,” she admitted. Yet the festival vibe of the book fair reignited her desire to actually purchase a book.

By the time Han Kang snagged the Nobel Prize in literature that October, “text hip” had already become a recognizable trend among younger readers and across bookish communities. But is this enthusiasm really about a return to reading in South Korea? Or is it just another lifestyle fad, more about looking literary than actually diving into books?

But is this enthusiasm really about a return to reading in South Korea? Or is it just another lifestyle fad, more about looking literary than actually diving into books?

The country’s authoritative biannual National Reading Survey paints a more complex picture than the common belief that Koreans don’t read. In fact, it suggests that 20- and 30-somethings have long been avid readers, which helps explain the massive turnout for events like the book fair.

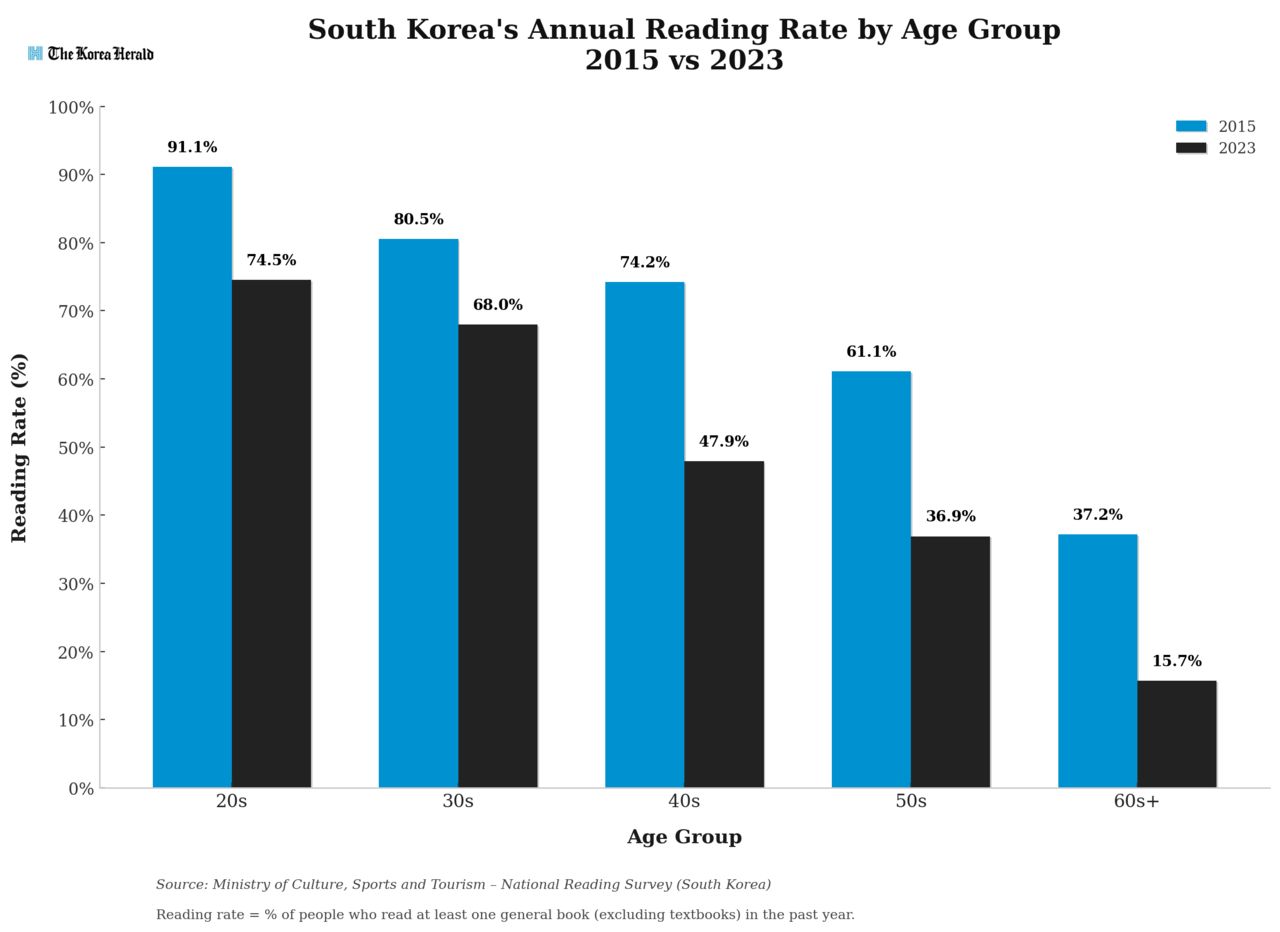

The most recent 2023 report showed 74.5 percent of Koreans in their 20s had read at least one book (excluding textbooks) in the past year. While this was still the highest rate among all age groups, it also marked a steep decline from 91.1 percent just eight years earlier. The number of physical books young Koreans consume annually plummeted during that same period, dropping from an average of 11.4 books per person to a mere 2.5.

What kept the numbers from nosediving even further was the rise of digital reading; e-book consumption among 20-somethings more than doubled in that time. Even with this digital boost, the overall trend confirms that young Koreans today are reading far fewer books than before.

Even with this digital boost, the overall trend confirms that young Koreans today are reading far fewer books than before.

But that doesn’t mean they’re not engaging with books at all.

Kim Nam-young, part of the National Reading Survey team at the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, told The Korea Herald that the survey only captures part of the story.

“To measure reading rates, we only count completed books,” she explained. “But we’re missing all the new ways people are interacting with books now. While this isn’t unique to Korea, it probably means we’re underestimating how many people are actively participating in reading culture.

At some point, we may need to completely rethink how we define reading.”

Yoo Ji-eun, a 29-year-old project manager in Seoul, considers herself part of the “text hip” generation. But she rarely reads books from cover to cover.

In April, she joined Hip Dok Club, a new reading initiative launched by Seoul Outdoor Library. The name blends “hip” and “reading,” and the concept struck a chord. All 10,000 membership slots were snatched up in under two hours, with the website initially crashing from the traffic.

Hip Dok Club rewards a wide range of book-related activities, from logging titles and posting quotes to sharing handwritten excerpts. Members earn points, level up, and score exclusive swag like reading lights and limited-edition merch. It’s less like a traditional book club and more like a literary social platform.

An outdoor club-exclusive chat with novelist Park Sang-young, author of “Love in the Big City,” drew hundreds. Yoo attended and said the experience rekindled her interest in Park’s novel, even though she hadn’t finished it the first time around. “It felt like a music festival,” she gushed. “People were there not just to read, but to experience books together.”

“It felt like a music festival,” she gushed. “People were there not just to read, but to experience books together.”

To skeptics, “text hip” and the craze over events like this might look like all style, no substance. But Baek Won-geun, former research head of the National Reading Survey and now director at the Book and Society Research Institute, isn’t so quick to dismiss it.

“Sure, it’s easy to roll your eyes,” Baek admitted. “But if buying book-related merch, joining clubs, or posting literary quotes eventually draws someone deeper into reading, then the trend is serving its purpose.”

Baek’s bigger worry is South Korea’s steep decline in reading among older adults. While other countries see a gradual drop-off, in South Korea, reading falls off a cliff as people age. Only 36.9 percent of Koreans in their 50s read even one book in the past year, and for those 60 and up, that number plummets to a measly 15.7 percent.

“The challenge is building lasting habits,” Baek explained. “The million-dollar question I’m interested in is this: will young people keep up their interest in reading, or ‘text hip’ as they call it, even as life gets busier and responsibilities pile up?”

Reading has long been treated as something we outgrow once school ends. But if “text hip” helps people see books as part of adult life, not just academic life, then the habit can survive the chaos. Not necessarily because we’re trying to be traditional bookworms, but because books can become part of how we live, said Gim Ji-min.

Most Commented